Event: Speech at Tulane University

Event: Speech at Tulane University

Location: Tulane University Field House, New Orleans, LA

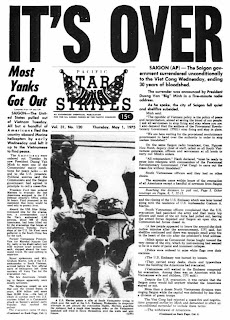

Description: President Gerald R. Ford declares that the Vietnam War “is finished as far as America is concerned” during his Convocation Address.

Date: April 23, 1975President Ford's Speech

on the Fall of Vietnam,

24 April 1975

[Following are excerpts from the text of a speech by President Ford as prepared for delivery to the student body of Tulane University:]

On Jan. 8, 1815, a monumental American victory was achieved here, the Battle of New Orleans. Louisiana had been a state for less than three years. But outnumbered American innovated and used the tactics of the frontier to defeat a veteran British force trained in the strategy of the Napoleonic Wars.

We had suffered humiliation and a measure of defeat in the War of 1812. Our national capital in Washington had been captured and burned. So the illustrious victory in the battle of New Orleans was a powerful restorative to national pride.

Yet the victory at New Orleans took place two weeks after the signing of the armistice in Europe. Thousands fled although a peace had been negotiated. The combatants had not gotten the word. Yet the epic struggle nevertheless restored America's pride.

Today America can again regain the sense of pride that existed before Vietnam. But it cannot be achieved by refighting a war that is finished — as far as America is concerned. The time has come to look forward to an agenda for the future, to unity, to binding up the nation's wounds and restoring it to health and optimistic self-confidence.

In New Orleans, a great battle was fought after a war was over. In New Orleans tonight we can begin a great national reconciliation. The first engagement must be with the problems of today — and of the future.

I ask tonight that we stop refighting the battles and recriminations of the past. I ask that we look now at what is right with America, at our possibilities and our potentialities for change, and growth, and achievement, and sharing. I ask that we accept the responsibilities of leadership as a good neighbor to all people and the enemy of none. I ask that we strive to become, in the finest American tradition, something more tomorrow than we are today.

Instead of addressing the image of America, I prefer to consider the reality of America. It is true that we have launched our bicentennial celebration without having achieved human perfection. But we have attained a remarkable self-governed society that possesses the flexibility and dynamism to grow and undertake an entirely new agenda — an agenda for America's third century.

I ask you today to join me in writing that agenda. I am determined as President to seek national rediscovery of the belief in ourselves that characterized the most creative periods in our history. The greatest challenge of creativity lies ahead.

We are saddened, indeed, by events in Indochina. But these events, tragic as they are, portend neither the end of the world nor of America's leadership in the world. Some seem to feel that if we do not succeed in everything everywhere, then we have succeeded, in nothing anywhere. I reject such polarized thinking. We can and should help others to help themselves. But the fate of responsible men and women everywhere, in the final decision, rests in their own hands.

Event: Republican congressional leadership briefing

Event: Republican congressional leadership briefing

Location: Cabinet Room

Description: President Gerald R. Ford briefs the leaders on the situation in Indochina. Defense Secretary James Schlesinger and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger are seated at the far end of the table.

Date: April 22, 1975 Event: Meeting to discuss the situation in Vietnam

Event: Meeting to discuss the situation in Vietnam

Location: The Oval Office

Description: President Gerald R. Ford meets with Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, Army Chief of Staff General Frederick Weyand, and Graham Martin, Ambassador to Vietnam.

Date: March 25, 1975 Công điện mật Ngoại Trưởng Henry Kissinger gữi Đại Sứ Hoa Kỳ MARTIN tại Việt Nam vào những ngày cuối tháng 4 năm 1975

Công điện mật Ngoại Trưởng Henry Kissinger gữi Đại Sứ Hoa Kỳ MARTIN tại Việt Nam vào những ngày cuối tháng 4 năm 1975 President Ford makes a late night phone call involving the evacuation of Saigon. April 28, 1975

President Ford makes a late night phone call involving the evacuation of Saigon. April 28, 1975 Event: Late night meeting Location: White House residence

Event: Late night meeting Location: White House residence

Description: President Gerald R. Ford discusses the evacuation of Saigon with Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and Deputy Assistant for National Security Affairs Brent Scowcroft.

Date: April 28, 1975

As Mrs. Ford looks on, President Ford discusses the evacuation of Saigon with national security advisers Henry Kissinger and Brent Scowcroft during an evening meeting in the White House residence. April 28, 1975

Description: President Ford carries a Vietnamese baby from “Clipper 1742," one of the Operation Babylift planes that transported approximately 325 South Vietnamese orphans from Saigon to the United States. San Francisco International Airport. April 5, 1975.

Description: President Ford carries a Vietnamese baby from “Clipper 1742," one of the Operation Babylift planes that transported approximately 325 South Vietnamese orphans from Saigon to the United States. San Francisco International Airport. April 5, 1975.

Nixon's War & Vietnamization: 1968-1973

Nixon's War & Vietnamization: 1968-1973

Vice President Nelson Rockefeller

Vice President Nelson Rockefeller

Event: Republican congressional leadership briefing

Event: Republican congressional leadership briefing Event: Meeting to discuss the situation in Vietnam

Event: Meeting to discuss the situation in Vietnam

President Ford makes a late night phone call involving the evacuation of Saigon. April 28, 1975

President Ford makes a late night phone call involving the evacuation of Saigon. April 28, 1975 Event: Late night meeting Location: White House residence

Event: Late night meeting Location: White House residence Description: President Ford carries a Vietnamese baby from “Clipper 1742," one of the Operation Babylift planes that transported approximately 325 South Vietnamese orphans from Saigon to the United States. San Francisco International Airport. April 5, 1975.

Description: President Ford carries a Vietnamese baby from “Clipper 1742," one of the Operation Babylift planes that transported approximately 325 South Vietnamese orphans from Saigon to the United States. San Francisco International Airport. April 5, 1975.